A new series of blog posts

If you live in a city, there are some things that may seem to be impossible, such as having a space to start a garden. Urban gardening, which is simply the practice of growing plants within the city limits, is having a resurrection in the past decade. In contrast to the rural, an urban garden is integrated into the city’s economic and ecological system1. It is also an essential part of TagTomat’s business.

“Globally, rapid urbanisation has drastically reduced the agricultural land and over half of the world’s population is living in urban areas and according to the United Nations by the year 2050 two thirds of the world’s inhabitants will become city dwellers.”2

Meanwhile, gardening is becoming a popular means of repurposing the unused urban spaces 1,3. If you live in a large city, you might not realise that urban gardeners are doing their work all around you. From small hanging window baskets on the balcony, raised beds in the yard to extensive rooftop gardens more people are stepping into the role of an urban gardener. This following article is dedicated to what is urban gardening and its role it plays in the city, mentioning some of the many initiatives established in Copenhagen.

Ancient history of urban gardening

In the present, with our extensive shipping networks, it’s simple to ship food from distant farms grown on the other side of the country or fly food from the other side of the world.

While urban gardening recently sees a comeback, it is not at all a new concept. The roots of urban gardening trace way back in the history of humans and has played a major role in cities. The history of urban gardening is fascinating, and I believe that having a better understanding of its history will allow us to educate others on its relevance while coming up with creative ways to integrate it in the modern cities.

According to a legend, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, considered one of the seven Ancient Wonders of the World, were built in the 6th century BCE. It may have been an oasis in the desert, a building covered with exotic trees and plants. Babylon, located about 80 km south from modern Baghdad in Iraq.4

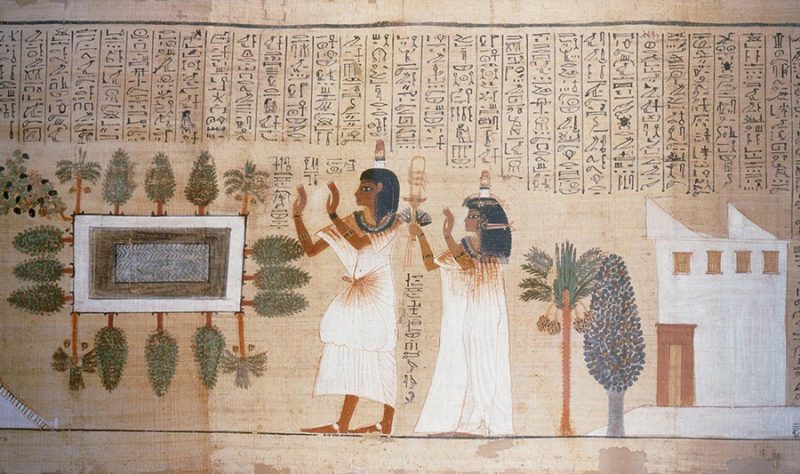

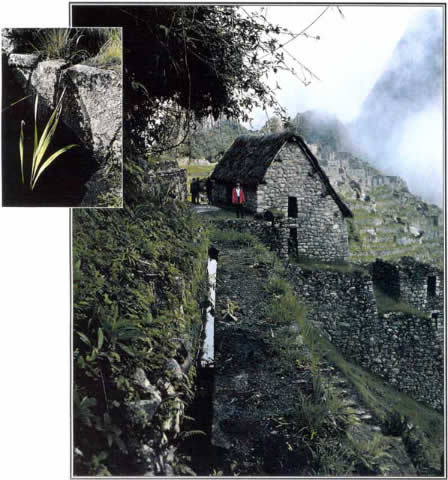

For thousands of years, cities and agriculture existed together. From community waste used in urbanised farming in ancient Egypt or vegetable beds and watering system in Machu Picchu.5

Urban gardening and the industrialisation era

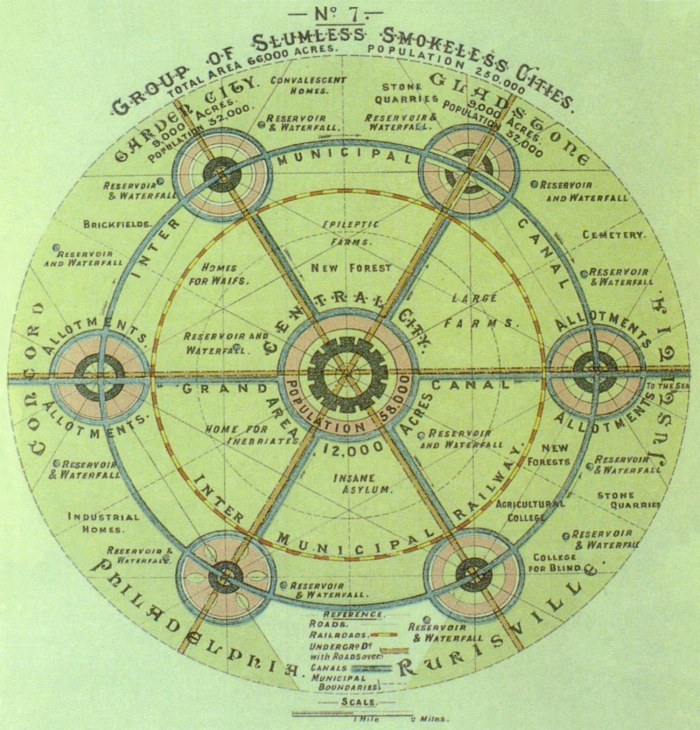

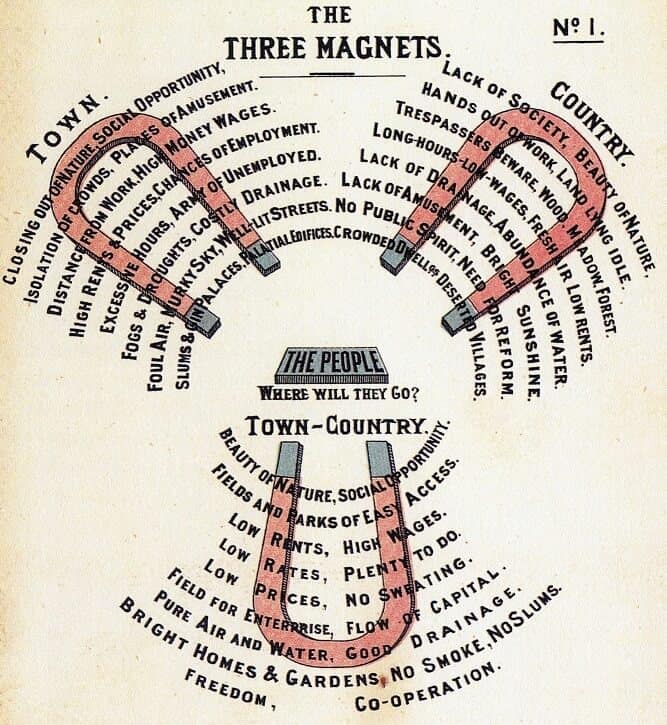

As the industrialisation was growing in Europe, urban architects were concerned about keeping cities sustainable and keep the city dwellers connected with nature. Notably, Sir Ebenezer Howard and his Garden City Movement in the 19th century. Howard’s idea was to react on the exponential growth of the cities and increased separation of its dwellers’ living space and nature. He designed a symmetrical map of seven towns, separated by large green areas, containing proportional areas of residences, industry and agriculture. This was supposed to lead to short commuting times, self-sustainable food security and short distance to green areas. He had no training in urban planning but excelled in creating places which he called “magnets” where people would want to live and work.6

The Garden City Concept was an effective plan for a better quality of life in overcrowded and unclean industrial driven towns which had degraded the natural environment and caused health problems.

First of such city was created in England – Letchworth Garden City. The city faced certain limitations when the ideals were translated into practice, though after decades the city was following Howard’s essential ideas. The city had a massive impact, inspiring numerous followers and is considered a cornerstone of modern urban planning.7

Urban gardening during the World Wars

In the United States, at the turn of the 20th century, a higher number of families than today were accustomed to working with the land in the form of farming and having kitchen or backyard garden. In general, food growing has been phased out as many people were moving to cities and its suburbs during the industrial revolution. When the First World War broke out, the US government asked citizens to keep to the earth. Everyone who could help with growing food was needed, for their families and for their communities.8

Similarly, during the second World War, families were asked to grow again. During this war, home gardens were prevalent. Around the country gardens could be found in front yards and backyards. In both cases, this war-time small scale farming was called Victory gardens in the United States.

“In fact, raising a small flock of chickens or having a pig in one’s backyard was the norm in urban setting.”8

It was reported that there were over 20 million gardens over the country which produced over 40 percent of US fresh produce. The small-scale gardens enabled communities to provide local foods as well as food to the military. Gardeners produced almost 8 million tons of food.9

“The Victory Garden program of World War II proved iconic, and has engaged the imagination of many today, who seek to transform the nation’s food system, one garden at a time.”10

Urban gardening since the World Wars

Turning from the 20th century and moving into the 21st century, there has been an increase in the number of farmers, especially those farming on a smaller land. In the same period there was seen an increase of number of farmers markets and community supported agriculture and roadside stands. In addition, a number of restaurants were buying from farmers directly and some had their own garden sources.8

To understand how urban gardening works it is important to introduce some of its grassroots initiatives. During the crisis in the 1970s many people had to ensure their self-sufficiency through cultivation in urban context. In these times the fastest growth of community gardening was seen as a response to these difficult times.

Community garden is another alternative manifestation of urban gardening. In their case the food production benefit is shifted also into strengthening of communities, bringing together citizens and different civil organisations.11 It is focused on food production as well as the relationship between people and the land. These gardens are located in public areas, supported by public and private stakeholders such as municipality or foundations. Most community gardens are accessible for all residents from the area or curious people.

“Nowadays, the diversity and creativity of today’s well-developed movement of Community Gardening can be seen in all major cities around the world.”11

In the 1980s, The Slow Food Movement emerged by a group of activists led by Carlo Petrini with the initial aim to defend local food cultures and good food as a protest against the growth of fast food culture in Italy. The movements’ emphasis on eating locally resulted in the phrase “locavore” for the ones who consumed food raised and harvested not too far from home.8 Over 30 years after its establishment, Slow Food has evolved into a significant global movement that promotes sustainable, local and high-quality food production and consumption around the world. Slow Food group and practices have emerged in more than 150 countries (slowfood web). Slow Food’s first festival, Terra Madre Nordic, was held in Copenhagen in 2018.

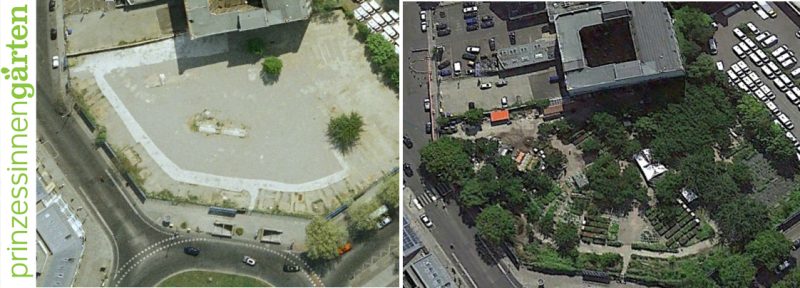

Berlin’s best-known urban gardening project started up in 2009. A non-profit organisation Nomadic Green launched a pilot project called Princess Gardens, a site which has been a wasteland over 60 years. This project beautifully demonstrates the power when hundreds of volunteers came together to make positive change. The people built movable recycled vegetable plots and planted vegetables, herbs and flowers (Princess Garden Web).

In London, Growing Underground is a project which transformed an abandoned World War II air raid bunker into a dynamic underground farm. The project started in 2015 after successful rounds of crowdfunding. Back during the nation’s darkest hours, the tunnels could have accommodated 8000 people. Now, with a total available space of 65000 square feet, they host stacks of sprouting greens. There are some 20 types of greens being grown. The fresh produced from the project are now stocked locally in supermarkets around London. Apart from cutting down of the transport costs, the growing is pesticide free as the germs having trouble to enter the complex and needs 70 percent less water than conventional farming methods.12

Power of urban gardening

In the following blog post you can expect more background and information about urban gardening and its benefits in overall well-being of its users as well as its contribution to the ecosystem.

Nowadays, urban gardens are used for more than just food insecurity. There is increased evidence that natural environments have important positive health outcomes. Engagement with both wild and cultivated natural places improves mood, self-esteem and reduces stress and anxiety.13

People find peace in having plants in their home or office, as well as fostering their social and emotional well-being. As plants require care and affection, people become more physically active as there is a need to maintain an urban garden, such as digging holes and watering the plants.

Promotes healthy eating, specifically studies suggest that fruit and vegetable consumption in urban setting gardens was relatively higher with gardeners in comparison to their non-gardening counterparts,14 which is leading to less risk of developing diet related chronic diseases. Furthermore, the urban garden acts as an important educational resource for its visitors. Aids recovery from stress, increase life satisfaction, promotes social contact between gardeners and provides space for physical activity.1 There is plenty of communal gardens where every person gets an area of their own to sow the plants.

References

1 Guitart, D., Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2012). Past results and future directions in urban community gardens research. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening, 11(4), 364–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ufug.2012.06.007

2 Around 2.5 billion more people will be living in cities by 2050, projects new UN report. (2018, May 16). Retrieved September 9, 2019, from UN DESA | United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs website: https://www.un.org/development/desa/en/news/population/2018-world-urbanization-prospects.html

3 Alaimo, K., Packnett, E., Miles, R. A., & Kruger, D. J. (2008). Fruit and Vegetable Intake among Urban Community Gardeners. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 40(2), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2006.12.003

4 Rosenberg, J. (n.d.). Did the Hanging Gardens of Babylon Really Exist? Retrieved September 9, 2019, from ThoughtCo website: https://www.thoughtco.com/the-hanging-gardens-of-babylon-1434533

5 MAMcIntosh. (2018, August 12). Urban Life in Ancient Egypt. Retrieved September 6, 2019, from https://brewminate.com/urban-life-in-ancient-egypt/

6 Garden City Movement (Urban Planning Concept) by Sir Ebenzer Howard. (2015, June 7). Retrieved September 2, 2019, from Planning Tank® website: https://planningtank.com/evolution-of-human-settlement/garden-city-movement-concept

7 O’Donnell, T. (2018, November 1). Ebenezer Howard and Letchworth: The First Garden City. Retrieved September 2, 2019, from Urban Utopias website: https://urbanutopias.net/2018/11/01/letchworth/

8 Andreatta, S. L. (2015). Through the Generations: Victory Gardens for Tomorrow’s Tables. Culture, Agriculture, Food and Environment, 37(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/cuag.12046

9 Lawson, L. J. (2005). City bountiful: a century of community gardening in America. University of California Press.

10 Hayden-Smith, R. (2014). Sowing the Seeds of Victory: American Gardening Programs of World War I. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland.

11 Trendov, N. M. (2018). Comparative study on the motivations that drive urban community gardens in Central Eastern Europe. Annals of Agrarian Science, 16(1), 85–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aasci.2017.10.003

12 Elkington, J. (2018, April 10). Something delicious is growing in the “sustainability underground” [Text]. Retrieved September 6, 2019, from GreenBiz website: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/something-delicious-growing-sustainability-underground

13 Wood, C. J., Pretty, J., & Griffin, M. (2016). A case–control study of the health and well-being benefits of allotment gardening. Journal of Public Health, 38(3), e336–e344. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv146

14 Audate, P. P., Fernandez, M. A., Cloutier, G., & Lebel, A. (2019). Scoping review of the impacts of urban agriculture on the determinants of health. BMC Public Health, 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6885-z

Author

Jan is a bachelor’s student of Global Nutrition and Health in Metropolitan University College in Copenhagen. The study takes a holistic approach to physical and mental health promotion. In autumn 2019, he is an intern at TagTomat and will be working with the term urban gardening in his upcoming bachelor’s thesis. He is passionate about sustainability and has growing interest in mental health promotion in urban context.

You can find Jan on LinkedIn.